I am a psychotherapist in Brooklyn, NY. Feel free to email me at atsheringlcsw@gmail.com if you would like to set up a consultation appointment.

I have often wondered whether especially those days when we are forced to remain idle are not precisely the days spend in the most profound activity. Whether our actions themselves, even if they do not take place until later, are nothing more than the last reverberations of a vast movement that occurs within us during idle days.

In any case, it is very important to be idle with confidence, with devotion, possibly even with joy. The days when even our hands do not stir are so exceptionally quiet that it is hardly possible to raise them without hearing a whole lot.”

“Idleness is fatal only to the mediocre.”

I heard a story that struck me as salient recently. A person I know told me a story from when they were a teenager. They had rented a house near the beach with some friends. Someone suggested that they jump into the ocean to kick off the weekend. It was a ridiculous idea. The ocean was freezing. But no one wanted to be the person who didn’t jump in.

The storyteller’s cadence slowed as it tends to do when a person is remembering something joyful. They said they could remember the moment right before they entered the water so clearly, as if their brain had said, “this moment is important. It will be one of the moments of your life.” The person said the moment was so pure, so innocent, so unlike what their life adult life had become. They wished more than anything to have that moment back.

That story gave me such a pang of nostalgia when I heard it, nostalgia for a time that I can’t even be sure really existed except in my imagination. It was a longing for a time when life was less confusing and the narrative of my life seemed ripe with possibility. It left me with a hollow feeling in my stomach.

I was shaken for days after. In my unconscious, I could feel my thoughts percolating. I knew something had been missing in my adult life. I couldn’t put into words, except that story of a teenager jumping into the ocean with their friends was somehow significant.

***

I have a lot of shame around my laziness. If I spend an afternoon strolling through the streets, lying on the grass or catching up on a tv show, I’m filled with guilt. Surely I could have spent my time more productively? Surely I could have finished the paperwork I’ve been putting off? But alas, I sin over and over again.

I used the word “sin” because I have the sense that there is a moral component to my shame. Work and productivity, in particular, take on an almost mythical, religious quality for Americans. Perhaps it’s the remnants of the Protestant work ethic that espoused the virtues of capitalism long ago. I can hear the voice of Max Weber in my shame. “I have not done enough. I am nothing if I am not productive.” Work somehow has become who am I. I am nothing without work.

Because I am a therapist, I am uniquely positioned to see the inner lives of the gentried class. A common theme emerges from my many sessions with them: great anxiety. It is an anxiety built not on a search for the basic needs of life, but built on a lack of “why” in their lives.

The “how” has been given to them by their culture-- advanced degrees in fields that are respected and well-payed. But these jobs are often stressful and require long hours, and these people have been worn down more and more by their daily grind. One person admitted me to recently, “I just don’t give a shit about this work. But I have to keep doing it.” This person was one of the more honest ones. Most of them continue to work and work for years upon years, trying to turn off the thought that maybe they aren’t content. Work becomes a compulsion, a mode to fulfill their American work ethic.

I’ve seen an emptiness take over many of them, hollowed-out people like survivors of a shipwreck. And the only solution often readily available to them is to consume. So they consume often without forethought but in search of pleasure to allay their emptiness. So they stroll out to nice restaurants and bars, watch the TV shows of the moment, drink themselves silly on Saturday nights and return to their Monday jobs, a constant Sisyphean treadmill of pleasure and avoiding pain.

I say all this without judgment. It’s what I observe not just in others but myself. I have struggled just like anyone to find my “why” to everyday life.

***

The story of the teenager jumping into the ocean continued to percolate in my thoughts over the next week. But I still had no answer.

Unsure what to do with this feeling, I found myself in Prospect Park on a Sunday. It was about midday, and I had some time to kill before I had to return home. I sat in the grass under the shade, as the sun was particularly vicious that day. My first instinct was to check my phone for work emails, twitter updates or to play some silly game.

But I stopped myself. Checking my phone felt compulsive as it always does. Instead, I just sat. I observed the barbecue nearby as the children played tag and squealed with joy. I felt the sun rays peeking through the giant Elm trees and the bristles of grass on my thighs. I took deep breaths and tried to be in the moment. I was calmer and less anxious than I had been since I heard the story.

It was then that I remembered what I had always known: the simple pleasures of being. I had spent so much recent time searching for a “why” to my everyday life, wracked with the same anxieties and shame as anyone else. But the answer to my “why,” it seemed, was that there was no answer, that to simply be in that moment and be alive was enough. Somehow I had disconnected from it through the inertia of stress and routines that we call everyday life. But here was joy again.

Sometimes anxiety would take over. And soon followed guilt. I felt like I was being lazy, just sitting on the grass on a Sunday afternoon, that I was doing something wrong spending my time like this. I had plenty of paperwork to do for work. I could be reaching out to psychiatrists to grow my professional network. I could be reading to improve myself. I could be at the gym, which I had missed for the past 3 days, to maintain my health. I wanted to feel in control of my life, to assuage my anxiety. But I knew better. I knew my longing to control was just a way to keep the anxiety at bay.

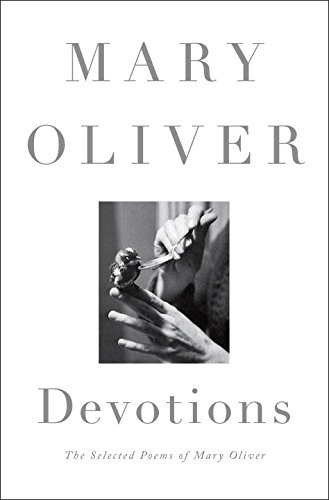

But at that moment I made the choice to let that go. I remembered a poem I had loved as a younger man and read it on my phone because it felt apt:

The Summer Day

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean-

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down-

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don't know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

—Mary Oliver

Reading it resonated just as it had the first time I read it. Maybe, as the poem says, it was prayer just to sit and watch and be. Maybe that’s what I needed to remember when life became too much. And maybe laziness was more valuable for living a joyful life than I had known.